FROM "MI REFLEJO" TO "PA’ MIS MUCHACHAS"

- Derrek Powell

- Jul 10, 2025

- 8 min read

CHRISTINA AGUILERA AND THE “RECLAMATION” OF LATINIDAD*

*Please note throughout this piece I do not use the terms “Latin”, “Latin American”, and “Latinx” interchangeably. “Latin” is a catch-all referencing the sociocultural dimensions of the Ibero-American diaspora, “Latin America/Latino” refers to citizens of Latin America (including Puerto Rico), and “Latinx” to U.S. born/naturalized citizens with Latin American ethnocultural roots.

On May 31, 2022, Sony Music Latin, the Miami-based record branch of Sony Entertainment dedicated to the promotion and distribution of Latin Music, released Aguilera, the ninth studio album performed by singer-songwriter Christina Aguilera. “Xtina” is one of the most recognizable vocalists of the last two centuries: Her four-octave vocal range, ability to sustain belted high notes, iconic scalar runs, and soulful timbre have earned her a communitarian recognition as the “Voice of a Generation” amongst millennials. I mean, who hasn’t tried to hit the opening run in “Ain’t No Other Man”. As evidenced by her continued success following her launch into the public eye in the late 1990s with her eponymous debut album, which featured three Billboard Hot 100 #1 singles and earned Xtina her first Grammy Award for Best New Artist (Grammy Awards, 2000), Aguilera’s vocals appear to transcend space, time, genre, and language.

Aguilera (2022) is the second Spanish-language studio album performed by the artist, being primarily described as a Latin pop album with heavy urbano influences, featuring elements of cumbia, tango, tropical, guaracha, and ranchera music. Reportedly, this collection marks the beginning of an upcoming trilogy of Latin albums recorded by Aguilera in Miami in early 2021 designed to pay tribute and connect her young children to the artist’s Latin American heritage. For long time fans, Aguilera’s Ecuadorian roots are common knowledge: She has been proclaiming #latinapride in interviews since the late 1990s in the face of repeated microaggressions and creative pressures to anglicize her surname, a common experience for Latinx artists like Ritchie Valens (né: Valenzuela). She goes on record stating: “I’m an Aguilera. I will always be an Aguilera. My father is from Ecuador and I’m very proud of that” (La Fuerza, Jan 2022). The album, much like its predecessor Mi Reflejo (2000) which topped the Billboard Top Latin Album charts for 19 consecutive weeks upon its release, was celebrated by consumers and critics alike, reaching the top-twenty on the U.S. Latin Pop Albums chart and earning Aguilera seven nominations at the upcoming 23rd Annual Latin Grammy Awards, marking her as the second-most-nominated female artist of the ceremony behind Spanish urban flamenco artist Rosalía (Grammy Awards, 2022).

The project has prompted criticism from prominent Latinx content creators/platforms who have published articles calling into question Aguilera’s motivations for an apparent “reclamation” of her Latinidad (see Balzano 2021). The arguments, in essence, critique Aguilera’s lack of Spanish-language projects since the turn of the century to imply that Xtina’s decision to do a Latin album in the contemporary is a promotional stunt motivated by the current global attention afforded to Latin artists like Bad Bunny. This type of argument brings to the foreground the privileges of Aguilera’s phenotype, citizenship, and unaccented English, all of which allow her to pass through the world unmarked, in addition to her lacking Spanish proficiency and needing a translator for Spanish-language interviews. Put simply, Aguilera (2022) is scrutinized as representing a white-passing, anglophone Latinx person adorning Latinidad for profit.

But Xtina has been publicly #proudlatina since her 1993 debut, and since she has released both Spanish-language collaborative tracks with prominent Latin American vocalists (i.e., “Hoy tengo ganas de ti” with Alejandro Fernández, 2013) and English-dominant tracks that incorporate Latin-based instrumental influences or Spanish code-switching (i.e., “Desnúdate” 2010). Popular music is a unique media form in that it presents an unparalleled ability to instill in its listeners notions of shared identification, of personally felt ethno-patriotism (see Frith 1987). Consumers tend to not like performers who feel inauthentic. But for Aguilera, expressing her Latinidad, connecting to her roots through Latin-based musical influences and performing in Spanish is an autobiographical expression of authenticity: “I think that we all own ourselves in a way that feels right to each individual and we are owed that” (La Fuerza, Jan 2022). If her connection to Latinness has always been publicly present, albeit from the margins, what exactly is she “reclaiming”? What was it about Aguilera (2022), or rather, about Xtina’s musically expressed connection to Latinidad in this instance, that warranted this criticism? Is it as simple as she’s just not “Latina enough”?

Reading these arguments, I find myself ruminating on questions of transnationalism, cultural authenticity, community membership requirements, and this concept of “reclamation”. Understanding these criticisms as they relate to racial and linguistic privilege requires a critical examination of the identity politics governing access to Latinidad. On the one hand, Latinidad is a politically entrenched media/marketing term that reduces (if not completely erases) the vast cultural heterogeneity of Latin America and the Ibero-American diaspora to commodify a collective “Latin” identity for U.S. and global consumption (see Cepeda 2010). Yet, interpersonally, Latinidad is the inherently transnational, hybrid abstraction of all that historically, culturally, and linguistically unifies the ethnonationalities of the Ibero-American diaspora. It’s the cultural similarities and specificities that relate the Puerto Rican, Brazilian, and Mexican experiences in processes of transnational/transcultural community formations in the face of White (Anglo-United Statesian) Supremacy.

Of course, individuals inevitably have varying degrees of expression, identification, and personal significance regarding their own Latinness, as well as distinct opinions about who can and cannot claim membership, with combinations of linguistic characteristics, ethnonational affiliations, and cultural knowledges as established membership criteria. To assert that all Latinx/Latin American individuals experience static degrees of cultural identification assigned at birth ignores the ways in which humans recalibrate their ethnocultural identities throughout their lifetimes according to circumstance and context.

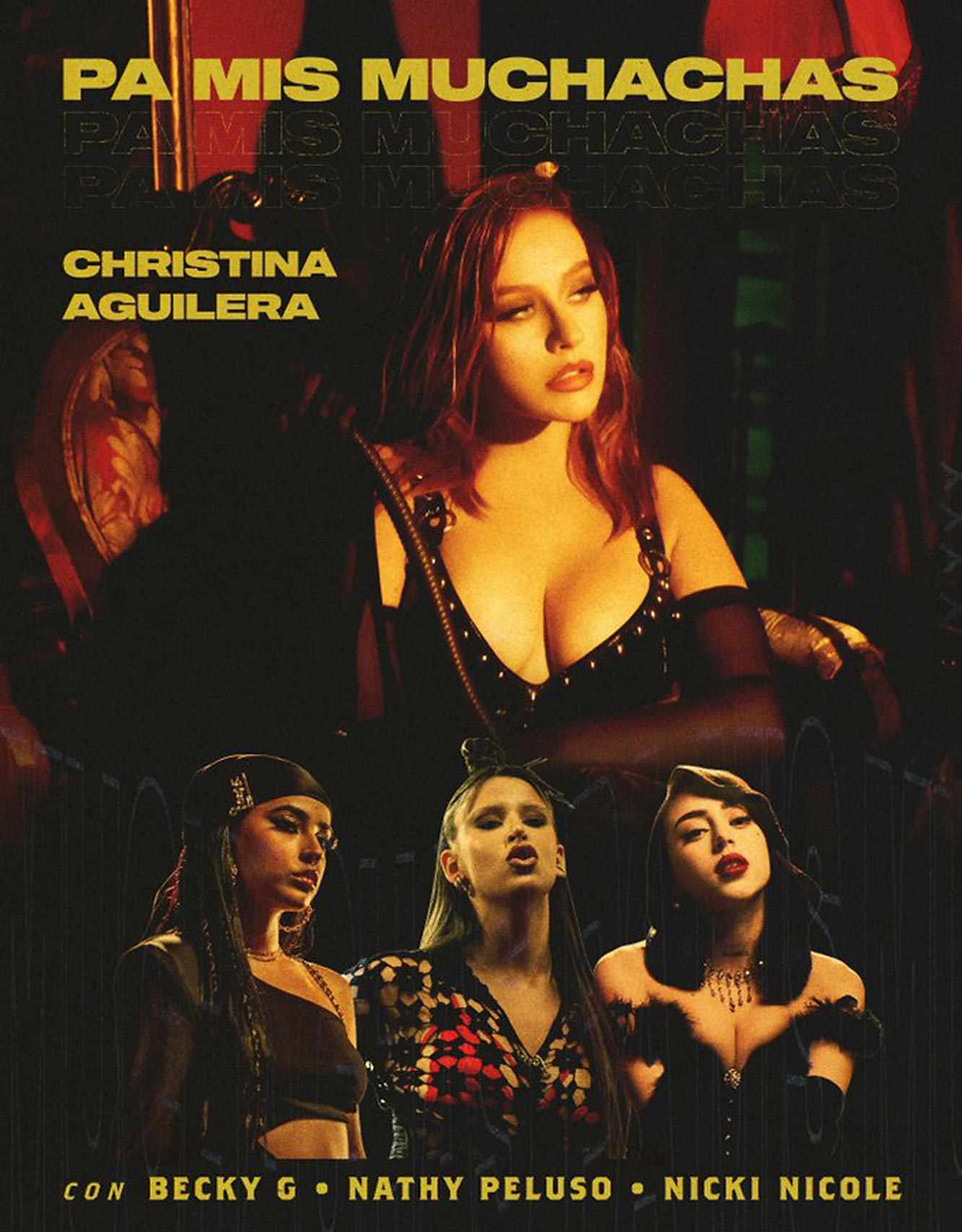

There is no absolute, objective way to be, have, or express Latinidad. In many cases, Latinx and Latin American artists have Latinidad thrust upon them in the sense that they are expected to represent su gente in the public eye (see Cepeda 2010). The critiques suggesting that Aguilera (and other Latinx peoples deemed “not Latin enough”) conveniently adorn Latinidad for commercial profit, and similarly those that target the same artists for not adorning enough Latinidad in other instances, obscure far more interesting questions. For example: What even is “Latin” music in the contemporary? The term is a catch-all category implemented by the music industry to encompass all musical stylings with Ibero-American instrumental origins, as well as all works (regardless of genre) that are performed in Spanish and Portuguese. Even focusing solely on Aguilera (2022) illuminates the diversity hidden within the category: Track 6 “La Reina” is a Mexican ranchera performance paying homage to the legendary Vicente Fernández, track 4 “Santo” featuring Puerto Rican rapper Ozuna is unmistakably a reggaetón production, and the promotion single “Pa’ Mis Muchachas”, featuring Mexican American Becky G and Argentines Nathy Peluso and Nicki Nicole, is a modern Cuban guaracha with urban and tango influences. The musicocultural hybridity of the stylings and featured artists on the album, combined with its conceived function as an artistic means to connect Aguilera’s children to their Latinness, thus begs the question: Whose heritage(s) exactly is Xtina homaging through this work?

In the 22 years since Mi Reflejo, the conditions for producing and distributing Latin music, and embodying mediated Latinidad overall, have shifted in the United States. Aguilera now releases music in a time where U.S. Latinx artists have the platform and resources to unapologetically express their Latinness sans anglicized filters, whereas Mi Reflejo was produced under conditions that essentially aimed to translate a successful English studio album into Spanish hoping to cross Xtina over into the Latin market. But there is something missing when works are interpreted in another language as opposed to original creations produced by teams who are authentic, cultural experts. Regarding the decision to sing in Spanish, Xtina states: “I have such a respect for the language. And it, it can’t translate. It’s so beautiful; it cannot be a strict translation into English” (Billboard, Nov. 2021). When reflecting on her experiences recording Aguilera, she expressed that she felt “humbled and grateful to be around the talent (musicians, artists, writers) for [the] album” (Billboard, Nov. 2021), and while she may be the forerunner, the creative talents (i.e., producer Rafa Arcaute) all contribute varying degrees of cultural and professional expertise to the album, (in)directly infusing the hybridity of Latinidad at the collection’s creative core. What distinguishes Aguilera from its predecessor is that it is an audio-visual album written and produced by Latinx and Latin American creatives for members of those same communities.

Moreover, Xtina represents a unique generation of Latinx in the United States context, a generation of individuals with Latin American roots whose direct cultural connection (whether familial or linguistic) to the homeland is diminished or severed due to circumstance (e.g., U.S. assimilationist pressures), but for whom the self-identification of Latinx still holds significance. Aguilera, when questioned about her desire to “reconnect” with her roots, invokes familiar narratives of Latinidad as being something genetically inherited through bloodlines, a naturalistic connection that bonds all members of the Ibero-American diaspora, stating:

“I represent a generation who heard Spanish growing up in the household, but after the parents get divorced, you stop hearing it, but it stays in you. You have the ear to go back to it… I have two incredible people who I work with who did help me on honing in on the words. It’s also tricky because, you know, every territory has a different way of speaking and different slang, and so I really reverted back to the way that I heard my father speak it.” (AP Archive 31 Jan 2022)

Does a connective, cultural rupture; a removal from place, language, or community, bar individuals like Aguilera from publicly reconnecting with their heritage in a way that is personally authentic? Does that invalidate the artistic and cultural authenticity of the work? Of course not, because being/doing “Latin” is not objective ontological existence: it’s variable praxis. Rather than viewing Aguilera as the commodification of identity for capital, critics should examine the work as a contemporary representation of the culminated transnational flows and influences that have come to represent an entire generation of second- and third-generation U.S. born Latinx peoples. A generation of Latinx people upon whom the specificities of Latinidad have been imposed through reductively packaged tropes informed by U.S. (Anglo) conceptions of what it means to look, be, and speak Latino.

Earlier I posed the question: Whose heritage(s) exactly is Xtina homaging through this work? The answer, as I see it, is simply her own, or rather, a U.S.-filtered model of Latin identification masquerading as pan-ethnic unity. Aguilera is not an Ecuadorian national, and according to her interviews she does not have a close relationship with her Latino father. Regardless, she was raised and socialized amongst the vibrant sounds, smells, and people who make up the Latinx millennial community. Aguilera is not supposed to be a reclamation of specifically Ecuadorian, or Puerto Rican, or Mexican roots. In fact, it’s not a “reclamation” at all. It is, instead, a compilation of U.S. Latinness, of transnational Latinidad, that exemplifies the beautiful hybridity that defines the category as told through the sounds (both musical and linguistically accented) of those back in the homelands as well as here in the U.S. Once again, Aguilera’s vocals transcend space, time, genre, and language.

Comments